Fugitive Slave Act Of 1850 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the

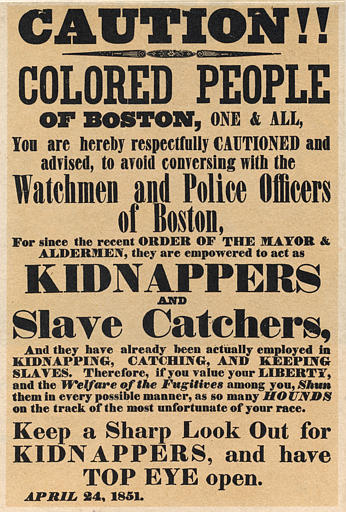

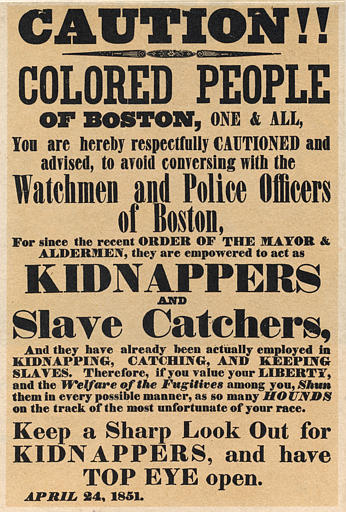

In response to the weakening of the original Fugitive Slave Act, Democratic Senator James M. Mason of Virginia drafted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which penalized officials who did not arrest someone allegedly escaping from slavery, and made them liable to a fine of $1,000 (). Law enforcement officials everywhere were required to arrest people suspected of escaping enslavement on as little as a

In response to the weakening of the original Fugitive Slave Act, Democratic Senator James M. Mason of Virginia drafted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which penalized officials who did not arrest someone allegedly escaping from slavery, and made them liable to a fine of $1,000 (). Law enforcement officials everywhere were required to arrest people suspected of escaping enslavement on as little as a

"Fugitive Slave Law" (2008)

*

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20081108152931/http://eserver.org/thoreau/slavery.html "Slavery in Massachusetts" by Henry David Thoreau

Runaway Slaves

a Primary Source Adventure featuring fugitive slave advertisements from the 1850s, hosted b

The Portal to Texas History

Serialized version of Uncle Tom's Cabin in The National Era by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fugitive Slave Act Of 1850 1850 in American politics 1850 in American law Extradition in the United States Presidency of Millard Fillmore Origins of the American Civil War United States federal slavery legislation Fugitive American slaves 31st United States Congress

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most controversial elements of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a slave power conspiracy. It required that all escaped slaves, upon capture, be returned to the slaver and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate. Abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

nicknamed it the "Bloodhound Bill", after the dogs

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it is derived from the extinct Pleistocene wolf, and the modern wolf is the dog's nearest living relative. Do ...

that were used to track down people fleeing from slavery.

The Act contributed to the growing polarization of the country over the issue of slavery, and was one of the factors that led to the Civil War.

Background

By 1843, several hundred enslaved people a year escaped to the North successfully, making slavery an unstable institution in the border states. The earlierFugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the US Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to also gi ...

was a Federal law that was written with the intent to enforce Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution, which required the return of escaped enslaved people. It sought to force the authorities in free states to return fugitives of enslavement to their enslavers.

Many Northern states wanted to disregard the Fugitive Slave Act. Some jurisdictions passed personal liberty laws

In the context of slavery in the United States, the personal liberty laws were laws passed by several U.S. states in the North to counter the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Different laws did this in different ways, including allowing j ...

, mandating a jury trial before alleged fugitive slaves could be moved; others forbade the use of local jails or the assistance of state officials in the arrest or return of alleged fugitive slaves. In some cases, juries refused to convict individuals who had been indicted under the Federal law.

The Missouri Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Missouri is the highest court in the state of Missouri. It was established in 1820 and is located at 207 West High Street in Jefferson City, Missouri. Missouri voters have approved changes in the state's constitution to give ...

routinely held with the laws of neighboring free states, that enslaved people who had been voluntarily transported by their enslavers into free states, with the intent of the enslavers' residing there permanently or indefinitely, gained their freedom as a result. The 1793 act dealt with enslaved people who escaped to free states without their enslavers' consent. The Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled, in ''Prigg v. Pennsylvania

''Prigg v. Pennsylvania'', 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539 (1842), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 precluded a Pennsylvania state law that prohibited blacks from being taken out of the free s ...

'' (1842), that states did not have to offer aid in the hunting or recapture of enslaved people, greatly weakening the law of 1793.

After 1840, the Black population of Cass County, Michigan

Cass County is a county in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 Census, the population was 51,589. Its county seat is Cassopolis.

Cass County is included in the South Bend– Mishawaka, IN-MI, Metropolitan Statistical Area which has a ...

, grew rapidly as families were attracted by white defiance of discriminatory laws, by numerous highly supportive Quakers, and by low-priced land. Free and escaping Blacks found Cass County a haven. Their good fortune attracted the attention of Southern slavers. In 1847 and 1849, planters from Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

and Boone counties, Kentucky led raids into Cass County in order to recapture people escaping slavery. The raids failed but the situation contributed to Southern demands in 1850 for passage of a strengthened fugitive slave act.

Southern politicians often exaggerated the number of people escaping enslavement, blaming the escapes on Northern abolitionists, whom they saw as stirring up their allegedly happy slaves, interfering with "Southern property rights". According to the ''Columbus'' eorgia''Enquirer'' of 1850, The support from Northerners for fugitive slaves caused more ill will between the North and the South than all the other causes put together.

New law

In response to the weakening of the original Fugitive Slave Act, Democratic Senator James M. Mason of Virginia drafted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which penalized officials who did not arrest someone allegedly escaping from slavery, and made them liable to a fine of $1,000 (). Law enforcement officials everywhere were required to arrest people suspected of escaping enslavement on as little as a

In response to the weakening of the original Fugitive Slave Act, Democratic Senator James M. Mason of Virginia drafted the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which penalized officials who did not arrest someone allegedly escaping from slavery, and made them liable to a fine of $1,000 (). Law enforcement officials everywhere were required to arrest people suspected of escaping enslavement on as little as a claimant

A plaintiff ( Π in legal shorthand) is the party who initiates a lawsuit (also known as an ''action'') before a court. By doing so, the plaintiff seeks a legal remedy. If this search is successful, the court will issue judgment in favor of the ...

's sworn testimony of ownership. was declared irrelevant, and the Commissioner before whom the fugitive from slavery was brought for a hearing—no jury was permitted, and the alleged refugee from enslavement could not testify—was compensated $10 if he found that the individual was proven a fugitive, and only $5 if he determined the proof to be insufficient. In addition, any person aiding a fugitive by providing food or shelter was subject to six months' imprisonment and a $1,000 fine. Officers who captured a fugitive from slavery were entitled to a bonus or promotion for their work.

Enslavers needed only to supply an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

to a Federal marshal to capture a fugitive from slavery. Since a suspected enslaved person was not eligible for a trial, the law resulted in the kidnapping and conscription of free Blacks into slavery, as purported fugitive slaves had no rights in court and could not defend themselves against accusations.

The Act adversely affected the prospects of escape from slavery, particularly in states close to the North. One study finds that while prices placed on enslaved people rose across the South in the years after 1850 it appears that "the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act increased prices in border states by 15% to 30% more than in states further south", illustrating how the Act altered the chance of successful escape.

According to abolitionist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, even in the supposedly safe refuge of Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

, "some of them are so alarmed that they tell me that they cannot sleep on account of either them or their wives and children. I can only say I think I have been enabled to do something to revive their broken spirits. I want all my family to imagine themselves in the same dreadul condition."

Judicial nullification

In 1855, theWisconsin Supreme Court

The Wisconsin Supreme Court is the highest appellate court in Wisconsin. The Supreme Court has jurisdiction over original actions, appeals from lower courts, and regulation or administration of the practice of law in Wisconsin.

Location

The Wi ...

became the only state high court to declare the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional, as a result of a case involving fugitive slave Joshua Glover __NOTOC__

Joshua Glover was a fugitive slave from St. Louis, Missouri, who sought asylum in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1852. Upon learning his whereabouts in 1854, slave owner Bennami Garland attempted to use the Fugitive Slave Act to recover him. Glo ...

and Sherman Booth

Sherman Miller Booth (September 25, 1812 – August 10, 1904) was an abolitionist, editor and politician in Wisconsin, and was instrumental in forming the Liberty Party, the Free Soil Party and the Republican Party. He became known nationally a ...

, who led efforts that thwarted Glover's recapture. In 1859 in ''Ableman v. Booth

''Ableman v. Booth'', 62 U.S. (21 How.) 506 (1859), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court unanimously held that state courts cannot issue rulings that contradict the decisions of federal courts,Hoiberg, Dale H. (2010) overt ...

,'' the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the state court.

Jury nullification

Jury nullification (US/UK), jury equity (UK), or a perverse verdict (UK) occurs when the jury in a criminal trial gives a not guilty verdict despite a defendant having clearly broken the law. The jury's reasons may include the belief that the ...

occurred as local Northern juries acquitted men accused of violating the law. Secretary of State Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

was a key supporter of the law as expressed in his famous "Seventh of March" speech. He wanted high-profile convictions. The jury nullifications ruined his presidential aspirations and his last-ditch efforts to find a compromise between North and South. Webster led the prosecution against men accused of rescuing Shadrach Minkins

Shadrach Minkins (c. 1814 – December 13, 1875) was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins.Collison (1998), p. 1. He is known fo ...

in 1851 from Boston officials who intended to return Minkins to slavery; the juries convicted none of the men. Webster sought to enforce a law that was extremely unpopular in the North, and his Whig Party passed him over again when they chose a presidential nominee in 1852.

Legislative nullification

In November 1850, the Vermont legislature passed the Habeas Corpus Law, requiring Vermont judicial and law enforcement officials to assist captured fugitive slaves. It also established a state judicial process, parallel to the federal process, for people accused of being fugitive slaves. This law rendered the federal Fugitive Slave Act effectively unenforceable in Vermont and caused a storm of controversy nationally. It was considered anullification

Nullification may refer to:

* Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution

* Nullification Crisis, the 1832 confront ...

of federal law, a concept popular in the South among states that wanted to nullify other aspects of federal law, and was part of highly charged debates over slavery. Noted poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier had called for such laws, and the Whittier controversy heightened pro-slavery reactions to the Vermont law. Virginia governor John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buchan ...

warned that nullification could push the South toward secession, while President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

threatened to use the army to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act in Vermont. No test events took place in Vermont, but the rhetoric of this flare-up echoed South Carolina's 1832 nullification crisis and Thomas Jefferson's 1798 Kentucky Resolutions

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued t ...

.

In February 1855, Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

's legislature

A legislature is an assembly with the authority to make law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its p ...

also passed a law prohibiting county jails from being used to detain recaptured slaves, directing county prosecutors to defend recaptured slaves, and entitling recaptured slaves to ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' and trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significant ...

. Other states to pass their own personal liberty laws include Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

, New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

.

Resistance in the North and other consequences

The Fugitive Slave Law brought the issue home to anti-slavery citizens in the North, as it made them and their institutions responsible for enforcing slavery. "Where before many in the North had little or no opinions or feelings on slavery, this law seemed to demand their direct assent to the practice of human bondage, and it galvanized Northern sentiments against slavery." Moderate abolitionists were faced with the immediate choice of defying what they believed to be an unjust law, or breaking with their own consciences and beliefs.Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

wrote ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U. ...

'' (1852) in response to the law.

Many abolitionists openly defied the law. Reverend Luther Lee, pastor of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a City (New York), city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffa ...

, wrote in 1855:

There were several instances of Northern communities putting words like these to action. Several years before, in the Jerry Rescue, Syracuse abolitionists freed by force a fugitive slave who was to be sent back to the South and successfully smuggled him to Canada. Thomas Sims

Thomas Sims was an African American who escaped from slavery in Georgia and fled to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1851. He was arrested the same year under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, had a court hearing, and was forced to return to enslavement. ...

and Anthony Burns were both captured fugitives who were part of unsuccessful attempts by opponents of the Fugitive Slave Law to use force to free them. Other famous examples include Shadrach Minkins

Shadrach Minkins (c. 1814 – December 13, 1875) was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins.Collison (1998), p. 1. He is known fo ...

in 1851 and Lucy Bagby in 1861, whose forcible return has been cited by historians as important and "allegorical". Pittsburgh abolitionists organized groups whose purpose was the seizure and release of any enslaved person passing through the city, as in the case of a free black servant of the Slaymaker family, erroneously the subject of a rescue by black waiters in a hotel dining room. If fugitives from slavery were captured and put on trial, abolitionists worked to defend them in trial, and if by chance the recaptured person had their freedom put up for a price, abolitionists worked to pay to free them. Other opponents, such as African-American leader Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Ross, March 10, 1913) was an American abolitionist and social activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 slaves, including family and friends, us ...

, simply treated the law as just another complication in their activities.

On April 5, 1859, Daniel Webster after being seized in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

, on the accusation that he was actually Daniel Dangerfield, an escaped slave from Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. Loudoun County's seat is Leesburg. Loudoun ...

, had a court hearing. The federal commissioner in Philadelphia, J. Cooke Longstreth, set him free because, in his opinion, it had not been proven that Daniel Webster was the fugitive slave. Webster promptly left for Canada.

Canada

One important consequence was that Canada, not the Northern free states, became the main destination for escaped slaves. The black population of Canada increased from 40,000 to 60,000 between 1850 and 1860, and many reached freedom by theUnderground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

. Notable black publishers, such as Henry Bibb

Henry Walton Bibb (May 10, 1815 in Shelby County, Kentucky – August 1,1854 in Windsor) was an American author and abolitionist who was born a slave. Bibb told his life story in his narrative ''The Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb: An American ...

and Mary Ann Shadd

Mary Ann Camberton Shadd Cary (October 9, 1823 – June 5, 1893) was an American-Canadian anti-slavery activist, journalist, publisher, teacher, and lawyer. She was the first black woman publisher in North America and the first woman publisher i ...

, created publications encouraging emigration to Canada. By 1855, an estimated 3,500 people among Canada's black population were fugitives from American slavery. In Pittsburgh, for example, during the September following the passage of the law, organized groups of escaped people, armed and sworn to "die rather than be taken back into slavery", set out for Canada, with more than 200 men leaving by the end of the month. The black population in New York City dropped by almost 2,000 from 1850 to 1855.

On the other hand, many Northern businessmen supported the law, due to their business ties with the Southern states. They founded the Union Safety Committee and raised thousands of dollars to promote their cause, which gained sway, particularly in New York City, and caused public opinion to shift somewhat towards supporting the law.

End of the Act

In the early stages of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Union had no established policy on people escaping from slavery. Many enslaved people left their plantations heading for Union lines, but in the early stages of the war, fugitives from slavery were often returned by Union forces to their enslavers.Noralee Frankel, "Breaking the Chain: 1860–1880", in Robin D. G. Kelley & Earl Lewis

Earl Lewis is the founding director of the Center for Social Solutions and professor of history at the University of Michigan. He was president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation from 2013 to 2018. Before his appointment as the president of the ...

(eds), ''To Make Our World Anew'' (Vol. I: A History of African Americans to 1880, Oxford University Press, 2000: paperback edn 2005), pp. 230–231. General Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

and some other Union generals, however, refused to recapture fugitives under the law because the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and the Confederacy were at war. He confiscated enslaved people as contraband of war and set them free, with the justification that the loss of labour would also damage the Confederacy. Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

allowed Butler to continue his policy, but countermanded broader directives issued by other Union commanders that freed all enslaved people in places under their control.

In August 1861, the U.S. Congress enacted the Confiscation Act, which barred enslavers from re-enslaving captured fugitives. The legislation, sponsored by Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull esta ...

, was passed on a near-unanimous vote and established military emancipation as official Union policy, but applied only to enslaved people used by rebel enslavers to support the Confederate cause.Rebecca E. Zietlow, ''The Forgotten Emancipator: James Mitchell Ashley and the Ideological Origins of Reconstruction'' (Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 97–98. Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

forces sometimes returned fugitives from slavery to enslavers until March 1862, when Congress enacted legislation barring Union forces from returning anyone to slavery. James Mitchell Ashley

James Mitchell Ashley (November 14, 1824September 16, 1896) was an American politician and abolitionist. A member of the Republican Party, Ashley served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio during the American Civ ...

proposed legislation to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, but the bill did not make it out of committee in 1863. Although the Union policy of confiscation and military emancipation had effectively superseded the operation of the Fugitive Slave Act,Don E. Fehrenbacher, ''The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government's Relations to Slavery'' (Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 250. the Fugitive Slave Act was only formally repealed in June 1864. The ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' hailed the repeal, writing: "The blood-red stain that has blotted the statute-book of the Republic is wiped out forever."

See also

*Fugitive slave laws in the United States

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

* ''Ableman v. Booth

''Ableman v. Booth'', 62 U.S. (21 How.) 506 (1859), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court unanimously held that state courts cannot issue rulings that contradict the decisions of federal courts,Hoiberg, Dale H. (2010) overt ...

''

* Contraband (American Civil War)

Contraband was a term commonly used in the US military during the American Civil War to describe a new status for certain people who escaped slavery or those who affiliated with Union forces. In August 1861, the Union Army and the US Congress ...

* Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

* Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring P ...

of 1850, Cazenovia, New York

* ''Prigg v. Pennsylvania

''Prigg v. Pennsylvania'', 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539 (1842), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 precluded a Pennsylvania state law that prohibited blacks from being taken out of the free s ...

''

* Slave Trade Act

Slave Trade Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States that relates to the slave trade.

The "See also" section lists other Slave Acts, laws, and international conventions which developed the conce ...

s

* Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

Incidents involving the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (in chronological order)

*Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring P ...

, August 1850, Cazenovia, New York

* The act passes Congress and is signed by the President, September 18, 1850

* Seizure and enslavement of James Hamlet, September 26, 1850, Williamsburg, New York

* Escape of Shadrach Minkins

Shadrach Minkins (c. 1814 – December 13, 1875) was an African-American fugitive slave from Virginia who escaped in 1850 and reached Boston. He also used the pseudonyms Frederick Wilkins and Frederick Jenkins.Collison (1998), p. 1. He is known fo ...

, February 1851, Boston

* Reenslavement of Thomas Sims

Thomas Sims was an African American who escaped from slavery in Georgia and fled to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1851. He was arrested the same year under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, had a court hearing, and was forced to return to enslavement. ...

, April 1851, Boston

* Christiana Riot

The Christiana Riot, also known as Christiana Resistance, Christiana Tragedy, or Christiana incident, was the successful armed resistance by free Blacks and escaped slaves to a raid led by a federal marshal to recover four escaped slaves owned b ...

, September 1851, Christiana, Pennsylvania

* Jerry Rescue, October 1851, Syracuse, New York

* Escape of Joshua Glover __NOTOC__

Joshua Glover was a fugitive slave from St. Louis, Missouri, who sought asylum in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1852. Upon learning his whereabouts in 1854, slave owner Bennami Garland attempted to use the Fugitive Slave Act to recover him. Glo ...

, March 1854, Milwaukee

* Reenslavement of Anthony Burns, May/June 1854, Boston

* Attempted reenslavement of Jane Johnson Jane Johnson may refer to:

* Jane Johnson (actress) (1706–1733), English actress

* Jane Johnson (slave) (c. 1814–1872), American slave who was center of a precedent-setting legal case

*Jane Johnson (writer)

Jane Johnson (born 1960) is an Engl ...

, July 1855, Philadelphia

* Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

The Oberlin–Wellington Rescue of 1858 in was a key event in the history of abolitionism in the United States. A '' cause celèbre'' and widely publicized, thanks in part to the new telegraph, it is one of the series of events leading up to Civi ...

, September 1858, Oberlin and Wellington, Ohio

* Escape of Charles Nalle, November 1860, Troy, New York

References

Sources

* * *"Fugitive Slave Law" (2008)

*

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20081108152931/http://eserver.org/thoreau/slavery.html "Slavery in Massachusetts" by Henry David Thoreau

Runaway Slaves

a Primary Source Adventure featuring fugitive slave advertisements from the 1850s, hosted b

The Portal to Texas History

Serialized version of Uncle Tom's Cabin in The National Era by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fugitive Slave Act Of 1850 1850 in American politics 1850 in American law Extradition in the United States Presidency of Millard Fillmore Origins of the American Civil War United States federal slavery legislation Fugitive American slaves 31st United States Congress